Rutki-Kossaki

Borough of Rutki, Zambrów District, Podlaskie VoivodshipType of place

The Jewish cemetery.Information about the crime

Prior to September 1939 there were approx. 2000 residents in Rutki with 40% being Jewish. (Wokół Jedwabnego, vol. II, 2002 p. 328)

The majority of the Jews from Rutki would die already in 1941, taken to the village of Kołaki where in a forest next to the railway station mass murders of the Jewish population brought from nearby villages happened. “In September 1941 approx. 1000 Jews from Rutki and Zambrów were shot to death by the Gestapo and military police.” (A chapter from the thematic catalogue, GKBZHwP Bulletin vol. VIII. (1956) p.134, art. 115)

“In the early hours on 6 September SS officers arrived in cars in Rutki and ordered the whole Jewish population to gather on the square. They were assisted by the Polish police. Very few Jews escaped. Almost all of them turned up on the square, partially because the town was well protected and partially because they were sure they would be relocated somewhere else. The SS officers left forty something labourers in Rutki. […] Altogether, approx. 70 Jews were left – when including those who worked in the village and those who were not present in Rutki on that day, almost 250 Jews remained. According to quite reliable sources, the other 450 were taken 8 km away from Rutki to the village of Gosie Małe near the train station in Kołaki. Graves had been already dug there. The Jews were placed next to the ditches in groups and shot from automatic guns. Small children had their heads banged against the trees and were thrown into the ditches. Few Jews who tried to escape where shot. Before the massacre everyone was completely undressed. After the massacre, the farmers from Gosie Małe were ordered to fill the ditches with soil.” (Wokół Jedwabnego, vol. II, 2002 p. 333)

The transport of Jews from Rutki to Kołaki is recalled by Jerzy, born in 1928: “[…] Many [Jews] were taken away. Germans put them on carts and took them somewhere to the forest. They had already dug ditches and they would shoot them and throw them in. The ground was apparently moving [because] some of them were still alive. [It was] somewhere near Kołaki in the forest. They were taking them naked, before they got there half of them froze because there were heavy frosts then.” (Rutki-Kossaki, 13 October 2017.)

The same event was described by Tadeusz, a former mayor of Rutki: “Germans came and where the square is now, there were cobblestones. They would gather Jews, give them table spoons and order them to clean the cobble. They were chasing them… And these Jews were escaping… […] They gathered them, cars arrived and they took all of them to the forest near the train station in Kołaki. […] I used to work for Germans, breaking stones. I was 12 years old and I was walking to work [and I saw] a German ushering Jews, about 50 of them. And they were taking them to Kołaki.” (Rutki-Kossaki, 13 October 2017.)

The fact of using Jews for humiliating work has been confirmed by an anonymous account of the Jewish fate in Rutki, kept in the Ringelblum’s Archive: “The whole Jewish population, apart from working craftspeople, was used for forced labour. And because there was almost no work in Rutki, the Jews were ordered to clean streets and the square, water grass etc. During work or after, they were often beaten with sticks. The work itself was only a derision of the Jewish population.” (Wokół Jedwabnego, vol. II, 2002 p. 330)

Nevertheless, the Jewish cemetery in Rutki also has its own tragic war history. “I know they also killed several Jews but which one of them [of the military policemen from the police station in Rutki], I don’t know. If they caught a Jew somewhere, they would kill him on the Jewish cemetery.” (Ds. 39/67, p. 107) One victim’s name is known: “I don’t remember the year when it happened but after the eviction of all the Jews from Rutki, a son of a Jew called Wierzba Major was hiding in Rutki. Wierzba Major was a furrier and I used to live in Rutki in a house owned by Wierzba. I don’t remember the name of his son but he would be about 18 years old then. Wierzba’s son was hiding in a pigsty among his father’s outbuildings. In my presence, two or three military policemen from the police station in Rutki […] captured the boy in the pigsty and took him to the Jewish cemetery which was about 200 metres from Wierzba’s house. Next, I heard gunshots coming from the cemetery. The boy didn’t came home and I’ve never seen him again. The military policemen buried the boy’s body on the cemetery by themselves – I heard about it from neighbours. […] A few days later I saw traces of a freshly dug ditch on the cemetery. Today there is a market when the Jewish cemetery used to be.” (Ds. 39/67, s. 25) This account is from 1975.

Probably the same event was described by another witness who testified in 1970s in front of the District Commission for the Investigation of Hitlerite Crimes in Białystok: “A military policeman called Blum shot a Jewish boy on the Jewish cemetery in Rutki.” (Ds. 39/67, p. 5).”

A murder of a Jewish man is also recalled by Tadeusz: “[…] One Jew was shot by a Polish man. He was killed here.” (Rutki-Kossaki, 13 October 2017.)

Moreover, in December 1943 eight Jews were captured in the borough of Rutki. They were shot to death by military police. Their bodies were buried on the Jewish cemetery.” (A chapter from the thematic catalogue, GKBZHwP Bulletin, vol. VIII, 1956, p.134, art. 128)

Bodies of 5 Jews murdered on 10 September 1939 in Mężenin were also brought to the Jewish cemetery in Rutki. Alongside other 12 people they were shot by Wehrmacht soldiers and buried in a field. The date of their exhumation and the second burial of their bodies remain unknown. (A chapter from the thematic catalogue, GKBZHwP Bulletin, vol. VIII, 1956, p.135, art. 127)

Currently there is no trace of the Jewish cemetery in Rutki, neither there is any plaque reminding about its existence. On 13 October 2017 representatives of the Rabbinic Commission and the Jewish Historical Institute conducted a site inspection in Rutki-Kossaki. It has been established that the Jewish cemetery was located between the current streets of Wojska Polskiego, Żytnia and Obwodowa. The eldest residents confirm the existence of a Jewish necropolis. Aforementioned Jerzy remembers that the deceased did not have stone graves but mounds. The cemetery was not fenced but the entrance gate was clearly visible.

After the war the cemetery was divided into smaller plots and sold to residents for property building.

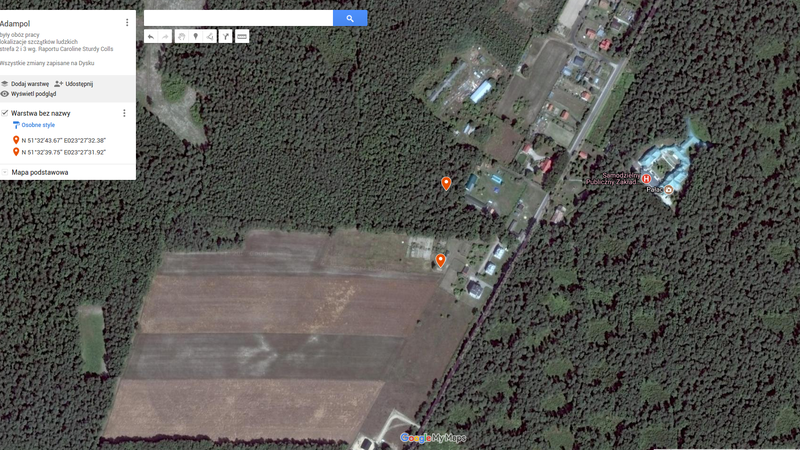

Adampol fotografia satelitarna 1e

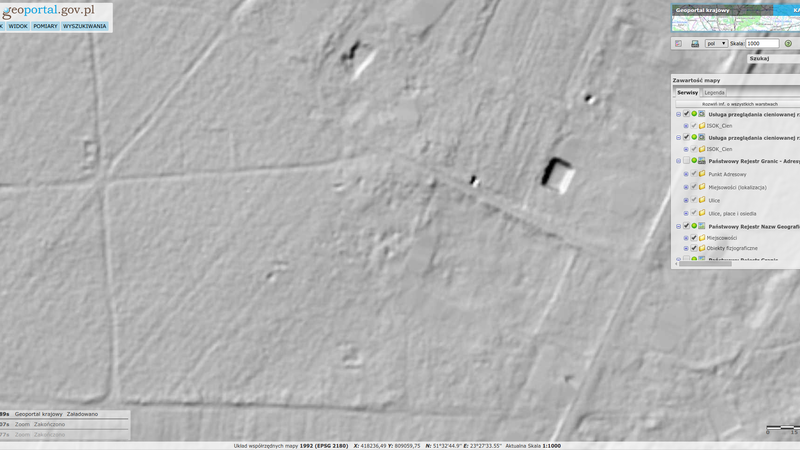

Adampol fotografia satelitarna 1e Adampol lidar 1b

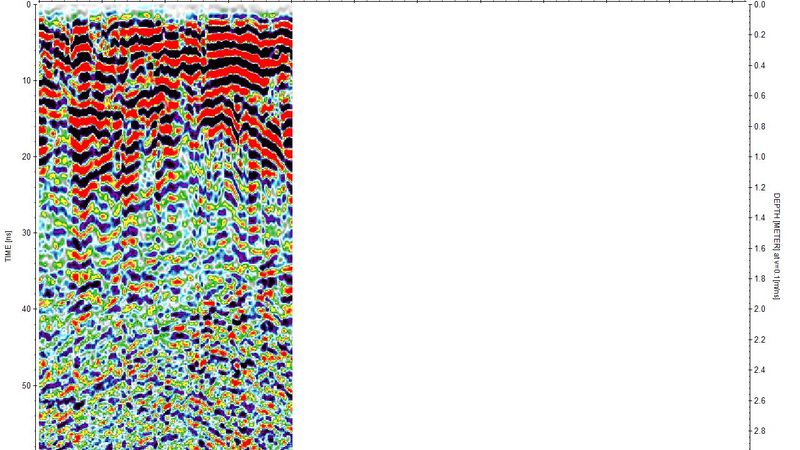

Adampol lidar 1b Adampol fotografia lotnicza 3, 29.05.1944

Adampol fotografia lotnicza 3, 29.05.1944 _B1A0801

_B1A0801 Blinów Pierwszy BLN10001

Blinów Pierwszy BLN10001Sources

Transkrypcje

Contact and cooperation

We are still looking for information on the identity of the victims and the location of Jewish graves in Rutki-Kossaki. If you know something more, write to us at the following address: fundacjazapomniane@gmail.com.

Bibliography

Recording of the Zapomniane Foundation (audio file), name: Jerzy [witness to the story], b. 1928, place of the residence: Rutki-Kossaki, subject and keywords: Jewish graves in Rutki-Kossaki, interviewed by Agnieszka Nieradko, Rutki-Kossaki, 13 October 2017.

Recording of the Zapomniane Foundation (audio file), name: Tadeusz, the former village administrator of Rutki [witness to the story], b. [lack of data], place of residence: Rutki-Kossaki, subject and keywords: Jewish graves in Rutki-Kossaki, interviewed by Agnieszka Nieradko, Rutki-Kossaki, 13 October 2017.

Cards from the thematic file of the Chief Commission for the Examination of German Crimes in Poland.

IPN Bi 1/687-689 (Ds.39.67).

Newsletter of the Jewish Historical Institute no. 38, p. 20.

Leszczyński K., Eksterminacja ludności na ziemiach polskich w latach 1939-1945, [in:] Newsletter of the Chief Commission for the Examination of German Crimes in Poland, 1956, vol. VIII, p. 115-204.

Wokół Jedwabnego, tom II, ed. Machcewicz P. i Perska K., Warsaw 2002.

In appreciation to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference) for supporting this research project. Through recovering the assets of the victims of the Holocaust, the Claims Conference enables organizations around the world to provide education about the Shoah and to preserve the memory of those who perished.

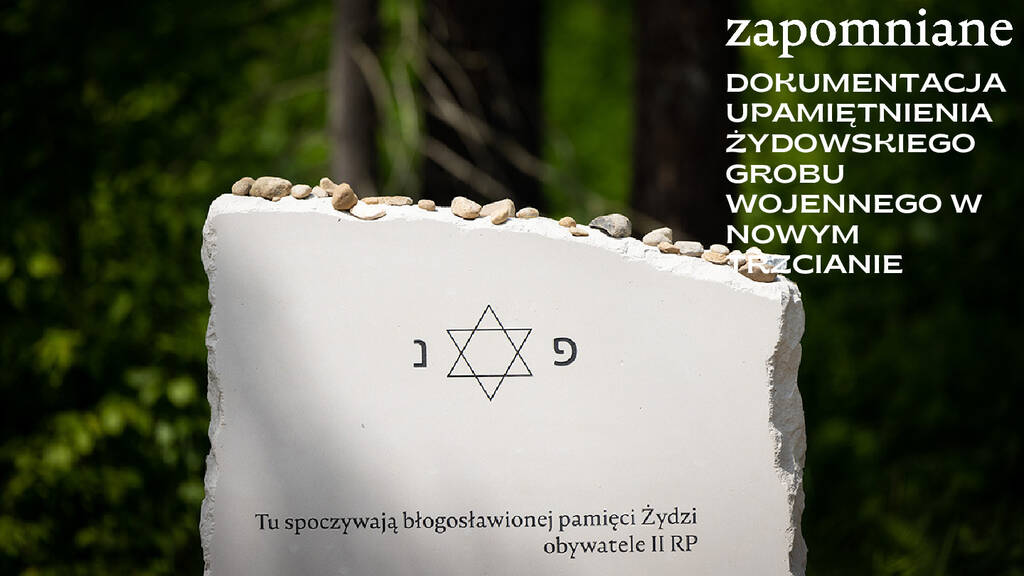

_Dokumentacja upamiętnienia w Nowym Trzcianie

_Dokumentacja upamiętnienia w Nowym Trzcianie Bełżyce transkrypcja nagrania

Bełżyce transkrypcja nagrania